In times of war, we need support more often than in times of peace. On the one hand, psychological support should be provided by professionals. On the other hand, it's just the way it is: all Ukrainians have become each other's psychotherapists.

Let's talk about emotional support mechanics. How does it work? What exactly are we supporting when we support a loved one? Why does it get easier sometimes, and sometimes it just becomes worse?

Let's start with the main thing: when we support a person, we actually support their psychological process that is happening right now.

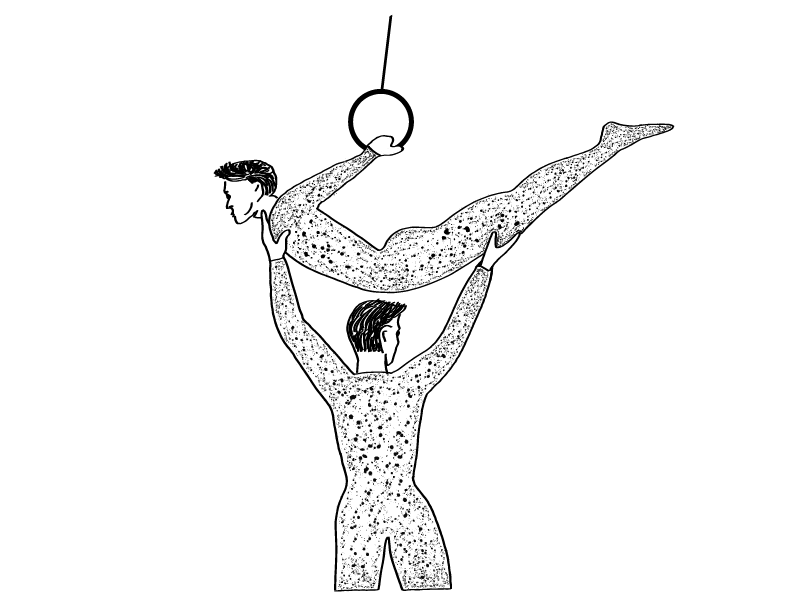

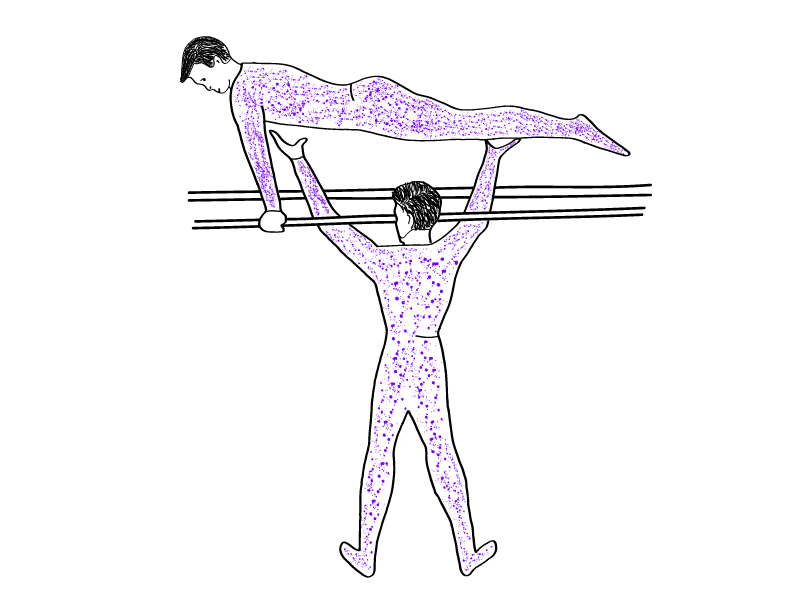

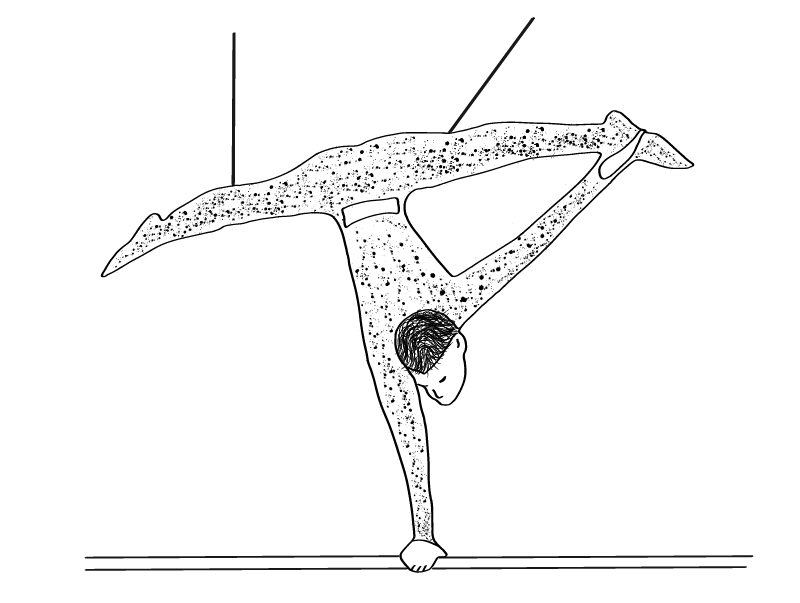

Psychology through sports metaphors

Psychological support, like support in sports, is to be there, provide supervision or make a little effort. Why? To help perform the exercise that the gymnast wants to perform.

What does it mean in practice? If a person is in the process of grieving and asks for support, we support the grieving process: we let them cry as much as they want, we don't argue, we don't convince, we don't try to cheer them up. Because "don't cry, life goes on" for a person in grief is not support precisely because it stops the grieving process, rather than supporting this process.

And how do I understand what process is happening now?

When a coach supports a gymnast, the coach must know exactly what exercise the gymnast performs, what exactly we support and safeguard. If the gymnast decided to do a somersault, and we are preparing for a jump, we are in trouble.

In psychotherapy, it can take hours to find out what process is happening now, what a person is experiencing and how exactly they are experiencing it. And psychologists are taught to do this.

Psychologists or not, but in any unclear situation it makes sense to ask.

"What would you like now? What could support you? What can I do for you now?”

But there is also a nuance here.

"If only I knew!"

When we are sad or stressed, we are often confused and disoriented. Not knowing what you want is normal. But it is still worth asking, because what if we are lucky and a person knows?

And if they don't? Then congratulations, now you are metaphorically supervising a gymnast, and you do not know what exercise they are performing, and they themself do not know either, and all this is happening in the dark and also you were not taught to do this.

It doesn't sound like fun. Are we obliged to guess the type of psychological process or spend time on careful questioning? Definitely not obliged. But we have empathy, sensitivity, intuition, and we love each other. We can say "I don't understand how you feel, but I'm here, I want to know more."

It is often worth it.

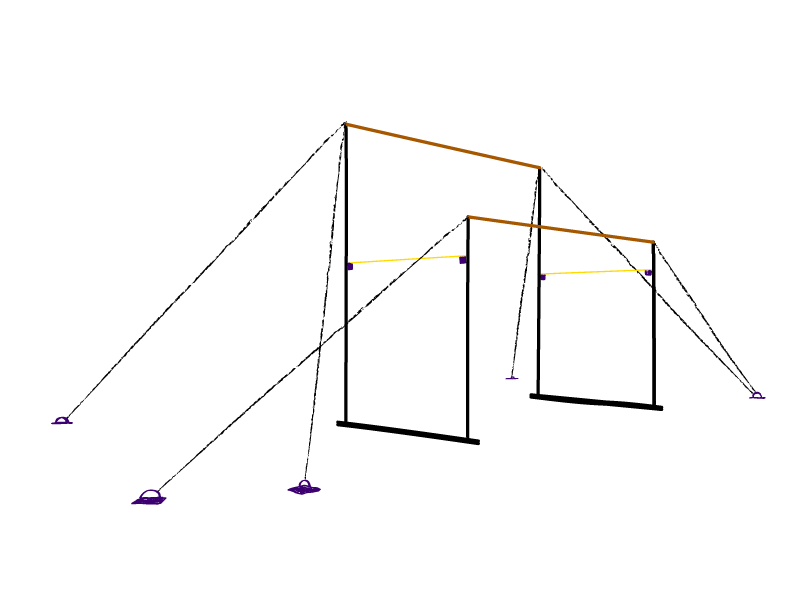

Safety techniques

While supporting others, we must take care of ourselves. And if we don't have the strength ourselves, it's okay to refuse support. If people always come to you for optimism and reassurance, and you no longer capable to provide this, it's okay to say, "I'm sorry, but I'm demotivated and discouraged today, too." The fact is that if we have no resources at all, then quality support will most likely not happen. There simply will not be enough energy. That also happens.

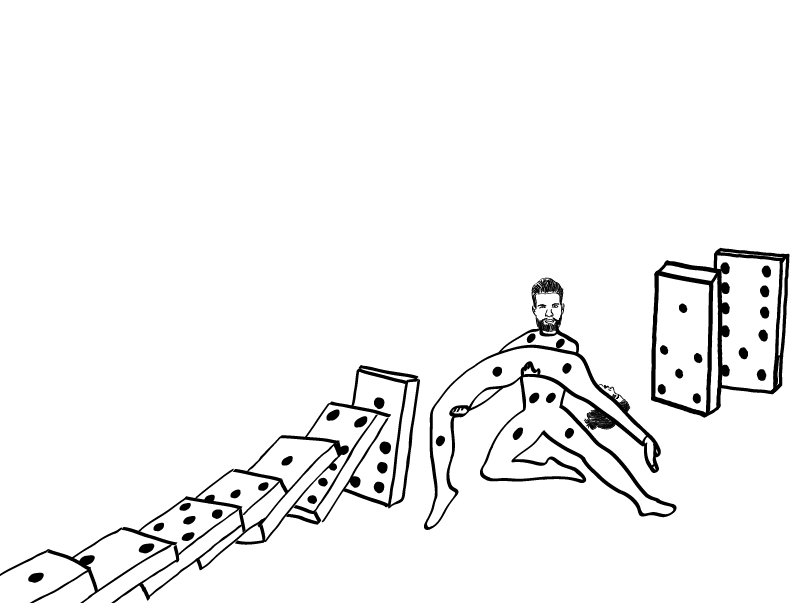

Big Ukrainian Domino

On the other hand, someone literally depends on us, someone is very dear to us. And there may not be an opportunity or desire to refuse support. Sometimes we support with the last bit of energy as if borrowing this energy from ourselves and hoping to find it later elsewhere.

That is why Ukrainian society during the war sometimes looks like dominoes: someone collapses on another one, another one goes for support to a more emotionally stable friend. Somewhere in this system of exhaustion, love and mutual support there are psychotherapists flaring up brightly, burning out:)

Ideally, it shouldn't be like this, but we are in the midst of the biggest war in Europe in the last 80 years.

"It's all too complicated and too scientific. Maybe we should just meet and have some wine?”

Maybe we should. But in fact, when we are just chatting over the drink, we also support a certain psychological process of a loved one: we a here for them in grief, or validate their dissatisfaction, or help to "chill out" and let off steam until it gets easier. We just do it intuitively or automatically. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't.

Consciously thinking about what is happening to a person, what process is happening, what is their need is always a good idea. If we already invest our time and attention in supporting another person, it is worth trying to do it to better.

How do I know if I managed to support?

By the feeling of relief that occurs in another person. It often happens like this:

— You helped me a lot, it was very important for me!

— But I didn't do anything, I just listened, I didn't even give any sensible advice.

But gratitude does not just happen: it means that we have really guessed what kind of support was needed.

And the opposite also happens: a lot of kind words were said, a lot of time, a lot of attention invested – and the person leaves annoyed, it has gotten worse. This is not "ungratefulness". It's just that everything is really individual.

But that doesn't mean we shouldn't keep trying.